Glauco Canalis — An intimate portrait of Naples’ coming-of-age suburban youth Glauco Canalis

During a trip to Naples, photographer Glauco Canalis came across kids enjoying the ritual of ‘o cippo ‘e Sant’Antuono, and something awoke in him. It’s harmless fun, but on first glance it may appear to be more sinister. Reminded of his own childhood recklessness, he set out to document them to offer an alternative depiction to the ones often given of Neapolitan youth. Canalis tells writer Gilda Bruno how, as he established a deeper connection with the boys as they came of age on the city’s streets, he uncovered a story of fragile masculinity, vulnerability, and the vivid hopes and dreams they harbored in spite of the complex socio-political environment they had grown up within.

During a trip to Naples, photographer Glauco Canalis came across kids enjoying the ritual of ‘o cippo ‘e Sant’Antuono, and something awoke in him. It’s harmless fun, but on first glance it may appear to be more sinister. Reminded of his own childhood recklessness, he set out to document them to offer an alternative depiction to the ones often given of Neapolitan youth. Canalis tells writer Gilda Bruno how, as he established a deeper connection with the boys as they came of age on the city’s streets, he uncovered a story of fragile masculinity, vulnerability, and the vivid hopes and dreams they harbored in spite of the complex socio-political environment they had grown up within.

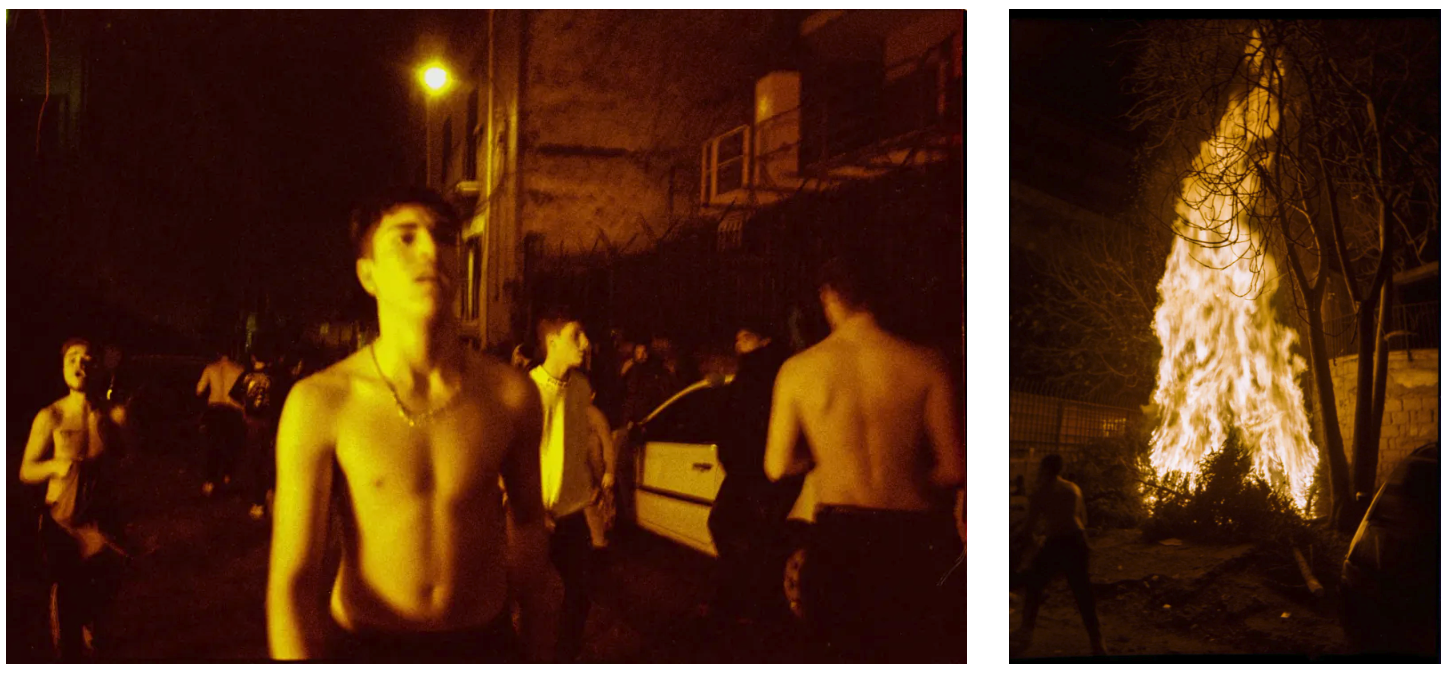

“The Darker the Night, the Brighter the Stars”, Glauco Canalis’ documentation of suburban teenagehood in Naples, stemmed from a simple question: “What the hell are they doing?” The photographer was in the Campanian city to work on a video clip when he came across swarms of children chaotically dragging huge Christmas trees on their backs. “It was January 2018,” he recalls. “They were trying to throw them behind a sheet of metal, but were so tiny that they struggled under the weight.” Watching them awakened in him memories of a childhood “spent on the streets doing all the crazy things kids do,” and Canalis began to dig deeper into it. For the following years, he focused his gaze on the youngsters of Torretta—a working-class suburb of the affluent Chiaia neighborhood—as they spent the run up to Christmas and the days following it storming its narrow alleys to collect any trees they could find and hide them in preparation for ‘o cippo ‘e Sant’Antuono (St. Anthony’s fire). Set aflame on the eve of January 17, this yearly bonfire is the final act of a three-month-long mission reuniting children in defense of one of Naples’ longest-standing customs.

In the original, centuries-old iteration of this pagan ritual, which marked the end of winter, farming families burnt domestic waste to protect their crops from the threats of evil spirits. For these youths’ parents and grandparents, “‘o cippo ‘e Sant’Antuono was a moment of popular communion,” Canalis says. “People would gather in a dedicated space, coming from all over the district, some carrying sweets to share with the rest, others just joining in with their cheeriness. It was a break in the ordinary: a time to feast, talk and build community.” Today, as the tradition is hindered by the city’s “suffocating” urban fabric, where parking lots and private gardens are built at the expense of public green spaces, its survival is under threat. But nothing, not even the police persecuting them, can stop the new generations from chasing its ancestral, contagious energy.

“Something in these children tells them they have to do it,” Canalis explains. Aged between six and 16, “many of them have dropped out of school or were raised by their mother alone, with their father in prison; others have never even had a room of their own.” For these teens, il cippo is more than an act of vandalism. It is a rite of passage imbuing them with an unconditional sense of purpose. Navigating a context deprived of opportunities, with criminality seizing on the fragility of Naples’ socially marginalized residents, the faces portrayed in “The Darker the Night, the Brighter the Stars” are those of children confronting life head on, searching for meaning and belonging even in the absence of positive role models to follow.